The Lighthouses of New Zealand

Source: Ross J O¨C (1975) The Lighthouses of New Zealand. Dunmore Press, Palmerston North.

INTRODUCTION

Among landsmen there are evidently many romantic notions about lighthouses. Witness the frequency with which they appear in song and story; the lighthouse shining across the bay providing the setting for the novelists' theme. The sheer majesty of some of the better known light towers captures the eyes of the artist and even more often, the photographer, and in his poem `Coastwise Lights of England' Rudyard Kipling has caught something of their human appeal.

A mariner however can be pardoned a certain affection for lighthouses, albeit his affection derives from more practical reasons. This volume is about the coastwise lights of New Zealand; of their construction, their administration and something of the men who man them and the ships which served them. The story begins with Pencarrow light and the construction period which really began with the Provincial Councils and the short-lived Marine Boards of the sixties.

There followed that vigorous nineteenth-century building programme of the Marine Department and more recently, the development of the automatic lights of this century. But it is not solely a story of construction, for around the lighthouses was also developed a well organised Lighthouse Service and a supply system based on the Government Steamers.

Much of the credit is due to a small number of engineers and master mariners who held office during these early years. The names of such men as Richard Aylmer, James Balfour, John Blackett and David Scott the engineers, and Captains Robert Johnson, John Fairchild and John Bollons the mariners crop up regularly in this volume. It is very largely due to their enterprise that by the turn of the century New Zealand was possessed of a well lighted coasted and a Lighthouse Service which was certainly as good and probably a good deal better than those of most western countries.

But these men were not alone. The coastwise lights would not have been built, nor maintained in a state of readiness were it not for those men whose lesser occupations did not engrave their names prominently in coastal history. These were the working parties who prepared the sites while living under canvas in the rudest conditions, built the lights and the Keepers' houses, often under weather conditions that can only be described as appalling. There were the crews of the Government Steamers who brought in building material and supplies, their boats' crews facing untold hazards on an exposed iron-bound coast. Then came the Keepers themselves who moved in when all was ready to serve under conditions of isolation that even today have no counterpart.

This last group may be a dying race, for nowadays, with automatic lights and monitoring systems, more and more lights fall into the unwatched category. Fortunately one of them, T.I. Clarke, has put pen to paper to record something of the life of a Lighthouse Keeper in his delightful book The Sea is my Neighbour. Tom Clarke writes with the authority of personal experience and this author hopes that the work he now presents will complement Mr Clarke's book by seeing the finished article from a mariner's point of view, the bridge of a ship.

This is a saga and a well deserved one, of the Marine Department. The author at once acknowledges the help he has received from the Marine Department Centennial History by E.R. Martin. That work has much to say on the lighthouses, but being one of a much broader nature, does not I suspect, give the Lighthouse Service the attention Mr Martin himself might have wished. A number of other volumes refer to certain lighthouses in passing and these the author has acknowledged in the bibliography.

The main sources of raw material for this volume have been the Annual Reports of the Marine Department since 1866, which the author has carefully perused through the courtesy of Miss E.A. Naish, the Marine Department Librarian. The other prolific source of detail has been the early Marine Department

Records, fortunately salvaged from a fire and catalogued by the ever helpful staff of the National Archives at the Record Centre in Lower Hutt.

In a country whose national wealth passes by sea the value of an efficient Lighthouse Service is incalculable in economic terms and for the untold number of ships and lives it has preserved from disaster. This volume is dedicated with great respect to the New Zealand Lighthouse Service; the men who built it and the men who man it.

Melling 1973

Bibliography

National Archives, Marine Department Records Series 8, Lighthouses

End of an Era

Change was in the air towards the end of the nineteenth but in no way was the passage of time more deeply reflected than in the loss of two of the most devoted and respected servants of the New Zealand Lighthouse Service.

The first of these was Captain Robert Johnson who died in hospital in August 1894 just twelve months after the death of his lifelong colleague, John Blackett. His had been a colourful career, 33 years of it devoted to the lighthouses of which he was the longest serving officer. He had served in a variety of appointments, all of them influential in the evolution of the light service of which it might be claimed he was the virtual father. He was succeeded by Captain A.G. Allman.

Four years later, on board his Tutanakei, Captain John Fairchild was accidentally killed when he was struck by a heavy shackle falling from aloft, tragically ending a career in the Government Steamers which, comparable to that of Johnson, had also begun in 1861. Both Houses of Parliament adjourned to attend his funeral and Richard John Seddon headed the mourners. With Fairchild died a maritime legend that was to be revived in the twentieth century by Captain John Bollons who in the same year succeeded to the command of the Hinemoa.

Coincidentally with the death of Captain Johnson, a change was made in lighthouse administration when all design and construction work was transferred to the Public Works Department, the Marine Department continuing to exercise responsibility for the light service through its Nautical Adviser and David Scott, the Lighthouse Artificer who remained with the department.

Very soon after he assumed office Captain Allman presided over the final act of a project which intermittently had engaged the attention of his predecessors for nearly 30 years. This was

the Snares Light about which nothing more had been done since Captain Johnson's visit with the Colonial delegates in 1891. In 1896, accomplanied by the new Marine Engineer W.H. Hales, Captain Allman again went south to reconsider the site for the proposed light.

It was an anticlimax. They confirmed the views of the 1891 delegates and in the following year, at a conference of Colonial Premiers in Hobart, New Zealand was invited to submit plans for the light. But once again, nothing was done. After years of debate and several expeditions to the island, time had wrought its own changes. Steam vessels no longer passed to the south of New Zealand as the windjammers had done in search of the favourable westerlies; the matter of the light on the Snares was quietly dropped, and the New Zealand Lighthouse Service was relieved of the prospect of constructing and manning what undoubtedly would have been the most isolated lighthouse in the world.

On rather firmer ground Captain Allman addressed himself to the matter of lights required in New Zealand. He placed a priority on lights at East Cape, and Kahurangi Point on the West Coast, but he also suggested that lights were needed at Cape Kidnappers, Kaikoura Peninsula, North Cape, Cape Brett and on Flat Point, 45 miles north-east of Palliser. These would be twentieth century lights but in the meantime, at the turn of the century, the Marine Department published a special coloured lighthouse chart of New Zealand. It was an impressive document showing a coastline now lighted with 28 principal lights and 17 harbour lights. It was a remarkable record of achievement and a silent testimony to Balfour and Blackett the engineers, to Johnson and Fairchild the Master Mariners and to David Scott the Artificer, a record of their life's work.

Cape Brett Light (1910)

After their first and somewhat unsuccessful experiments with unattended lights at Cape Jackson and Tuahine, the Marine Department turned their attention to revolving lights. It was not a new concept. It has already been shown that the first light on Pencarrow had been designed as a revolving light, but owing to mechanical faults had appeared as a fixed light.

The first successful revolving light was at Dog Island and, like most of its kind, it was actuated by a clockwork mechanism controlled by a huge weight which descended within the tower. It was an additional task of the Keepers at revolving lights to wind the mechanism up each hour.

There were certain limitations to these early revolving lights. It is not generally realised that the average lantern weighed several tons and a revolving light which moved on a system of wheels or ball bearings required a strong mechanism to keep it moving around its circular track. The shortcomings of the clockwork systems restricted both the speed of revolution and the weight of the optical system that could be placed in the lantern.

An invention of the late nineteenth century which altered this situation was that of supporting the lantern on a mercury float instead of wheels, a simple enough concept that at once presented several advantages. One was that the speed of revolution could be hastened, giving a faster flashing character; the other was that the superimposed lantern could be of increased weight

to accommodate a more powerful light. Lastly, since only the pressure of a finger was required to set the lamp in motion, a motor of much smaller proportion was needed.

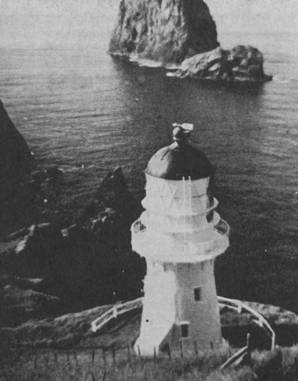

Cape Brett Light

The first of these mercury float lights was introduced on Cape Brett. The Nautical Adviser had proposed a light here in 1896, but it was still not erected in 1907 when the Secretary for Marine pointed out that there was no light between Cape Maria Van Diemen and Moko Hinau and he described Cape Brett as `the most wanted light in the Colony'.

When, however, they were consulted in the following year, the Shipmasters' Association were not so certain. Some preferred the Poor Knights or the Cavalli Islands, and it was Captain Bollons, sent to investigate in the Hinemoa, who settled on the site.

Far remote from roads and 400 feet up on a steep rocky shore, Cape Brett Light presented as many construction problems as the `rock' sites such as The Brothers or Cuvier islands. A solid landing block of concrete surmounted by a crane had first to be built; then a tramway to winch material up the slope. Everything had to be brought in by sea including the sections of a 35-foot iron tower built at the Thames works of the Judd Engineering Company.

David Scott supervised the work which went on through 1909, and when Cape Brett was finally lit on 21 February 1910 it was Scott's last lighthouse. After over thirty years of service as Lighthouse Artificer in which he had supervised the erection of lights on the most difficult places on the coast, Scott retired in 1911. No construction task seemed insurmountable to this man who thoroughly deserves his place in lighthouse history. He had survived the most incredibly dangerous tasks allotted to him over so many years; and four years after he retired he was killed when he fell from a train.

His last light, fitted with its mercury float system, is typical of the new generation of lights it introduced, a powerful light visible for 20 miles and flashing twice every thirty seconds. Cape Brett has since been electrified with diesel generators, but its isolation still means that its two Keepers and their families must be supplied by sea from Russell and their stores are still hauled up by David Scott's tramway.

David Scott

Excerpt:

Although time would bring its inevitable changes in the period, for much of it the New Zealand Light Service continued to be developed by its two principal architects, John Blackett and Robert Johnson.

They were joined in 1880 by another officer, David Scott who, as Lighthouse Artificer, was responsible for the on-site supervision of all construction and repair work. Although never apparently classified as an engineer, Scott's duties as Artificer are difficult to define, for they fell somewhere between that of engineer and foreman of works, but whatever his status he is accountable in lighthouse history for the remarkable tenacity of purpose and ingenuity with which he accomplished miracles of construction at sites which would even confound a modern engineer.